Perhaps it is negative, but the first question I ask myself before purchasing a share is: Well, yes, but is it overvalued? It is very difficult for non-experts (like me) to find shares that clearly offer very good value, but it can be easier to identify the more egregiously overpriced shares.

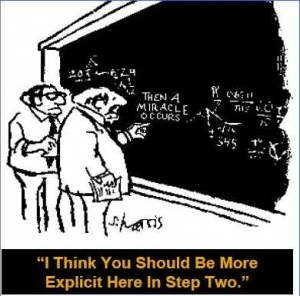

There is a range of rules-of-thumb that can help to identify the blatant hot air balloons. In isolation, these rules-of-thumb are probably all simplistic and meaningless, but if you string enough of them together they begin to form a safety net. One such rule-of-thumb is Ben Graham’s famous intrinsic value formula. There is plenty written about this elsewhere on the Web (see the references at the bottom of this post), but I think the important thing is that you should not in any way expect this formula to be anything more than a tool to eliminate some shares, as prospective purchases, or to flag others as being worthy of further thought.

What is intrinsic value?

Ben Graham defines Intrinsic value, as follows:

“Intrinsic value represents what an investor can get out of a company, and book value represents what has been put into the company.”

Warren Buffett, in the Berkshire Hathaway Owner’s Manual, uses the example of an education to illustrate this concept:

“Think of an education’s cost as its ‘book value’. If this cost is to be accurate, it should include the earnings that were foregone by the student because he chose college rather than a job.

For this exercise, we will ignore the important non-economic benefits of an education and focus strictly on its economic value. First, we must estimate the earnings that the graduate will receive over his lifetime and subtract from that figure an estimate of what he would have earned had he lacked his education. That gives us an excess earnings figure, which must then be discounted, at an appropriate interest rate, back to graduation date. The dollar result equals the intrinsic value of the education.

Some graduates will find that the book value of their education exceeds its intrinsic value, which means that whoever paid for the education didn’t get his money’s worth. In other cases, the intrinsic value of an education will far exceed its book value, a result that proves capital was wisely deployed. In all cases, what is clear is that book value is meaningless as in indicator of intrinsic value.”

Warning points to note

Why is this not a one-stop shop? There are several reasons, not least, as Joshua Kennon points out, although the formula would have made horse and buggy manufacturers look good value on an intrinsic value basis, it wouldn’t have told you that they would shortly become obsolete! The formula also takes no account of a company’s level of capital intensity, debt, dividend history, or enterprise size, most of which are other factors that Graham recommended be considered before a share purchase. Furthermore, the version of the formula that I show below takes no account of interest rates, although Graham did revise the formula in later years to address this (see References 2 or 3 below, if interested). I use the original version because that is the version in my edition of the Intelligent Investor–I might look at the later version in a future post.

Finally, to quote BG himself in an endnote to his Intelligent Investor “Note that we do not suggest that this formula gives the ‘true value’ of a growth stock, but only that it approximates the results of the more elaborate calculations in vogue.”

But at last…

Having disclaimed the life out of it, here is the famous Benjamin Graham formula (original version):

Value = Current (Normal) Earnings X (8.5 plus twice the expected annual growth rate)

The annual growth rate required by BG was the expected growth rate for the next seven to ten years. The best data source I can find to use for this is Morningstar’s Valuation tab, which if you click Wall Street Estimates, provides a five-year analyst growth forecast. Due to the extra few years of forecast required by BG, and analysts’ traditional over-enthusiasm, I will lop 25% off this figure.

8.5 was Graham’s estimate of a fair price/earnings ratio for a no-growth company.

Both Wikipedia and Joshua Kennon describe how you can apply this formula to a buy-sell decision by calculating a Relative Graham Value (RGV), where an RGV of less than one indicates that the share price is overvalued and and RGV of greater than one indicates a share price that appears reasonable and is worthy of further investigation. This formula is as follows:

RGV = Value/Price

Application

Here is how the formula would be applied to Altria, Diageo and IBM:

Altria Value: 2.26 X (8.5 + (2 X 4.8)) = $40.90

Altria Current Price: 38.25

Altria RGV: 1.07

Verdict: Slightly better than fair value.

Diageo Value: 104.4 X (8.5 + (2 X 4.5)) = 1827p

Diageo Current Price: 1910p

Diageo RGV: 0.96

Verdict: Sadly, slightly overvalued.

IBM Value: 14.94 X (8.5 + (2 X 6.6)) = 324.2

IBM Current Price: 197.02

IBM RGV: 1.65

Verdict: Interestingly, undervalued.

References

- Intelligent Investor, Chapter 11

- Wikipedia

- Joshua Kennon

Disclosure: Long MO, DGE, IBM

Disclaimer: This post is not a recommendation to either buy or sell. Please consult your investment advisor.